W

ith a climate neutral pro-

file, which also left its

marks on the rice fields,

Brazil is recovering its nor-

mal production volumes

in the 2016/17 growing season, after regis-

tering historical losses in the previous year’s

season, brought about by the El Niño phe-

nomenon. The March report by the National

FoodSupplyAgency (Conab) points toapos-

sible12.9%increase in the total volume tobe

harvested, a jump of 1.36 million tons, from

10.603million to11.966million tons.

The growth is based on the recovery of

earnings, despite the 0.8-percent drop in

seeded area, from 2.008 million hectares to

1.991millionhectares.“Plantingsinhighlands

and dry lands are on the decline because the

farmers can opt for the soybean/corn succes-

sion, more profitable, especially in the Cen-

ter-West and Southeast. This is generating

a concentration of upwards of 80% of rice

farming in the South”, explains Carlos Magri

Ferreira, socio-economist with Embrapa Rice

andBeans,inSantoAntôniodeGoiás(GO).

Productivity per hectare should soar

The picture released in March 2017 by

the Conab points to a 5.6-percent drop in

the harvest of dry land rice in Brazil, from

1.236to1.167milliontons.Theseededarea

fell 10.8%: from 608.7 thousand hectares

in the 2015/16 growing season 543.1 thou-

sand hectares were cultivated. It means a

reduction of 65.6 thousand hectares. The

increase of 117 kilograms per hectare, or

5.8%,inproductivity,upto2,147kilograms,

mitigates the smaller crop in thehighlands.

Mato Grosso, with 473.6 thousand

tons ready to be harvested from137 thou-

sand hectares, is the leading dry land rice

producer, followed by Maranhão (214.5

thousand tons, on 160.7 thousand hect-

ares) and Rondônia (121.8 thousand tons

and 40 thousand hectares). The highest

productivity in this agronomic model is

reached by Goiás, with an average of 3.9

thousand kilograms per hectare. Minas

Gerais has the lowest performance, where

the subsistence fields produce no more

than 850 kilograms per hectare.

n

n

n

Dry land versus irrigated

There isbig technological disparitybetween theBrazilian irrigated rice fields, a reference in theAmericas, oneof thehighest productiv-

ity rates in theworld, and in the dry land systems. The latter are still very primitive and subsistence oriented. The highlandmodel, where

genetics andmanagement technology are part of the system, also remains below the results achieved in irrigated fields, whether for the

existing technology transference problems, or for cultural aspects or, perhaps, for the objective of rice farming in these regions, generally

geared towardopeningupnewland toagricultureor for the recoveryof degradedpastureland. “If theaimdiffers fromcultivating rice, but

covering thecost of improving the land for other economicpurposes, the result isnot expressive. But thereareprofessional rice farmers in

these regions,well organizedandmakingprofits fromthis crop”, explainsCarlosMagri Ferreira, fromEmbrapaRiceandBeans.

n

n

n

Disparity

Brazil’scropmakesagood

recoveryinvolume,butstillremains

distantfromtheprofitabilityrates

expectedbymostofthefarmers

13.8%intheseason,onaccountofthefavor-

able weather conditions. “Brazil will reach

an average of 6,010 kilograms per hect-

are, almost 800 kilograms more than in the

2015/16 growing season. Climate and tech-

nologymake thedifference”, says SérgioRo-

berto dos Santos Júnior, Conab analyst.

Official statistics show that 81.6% of the

Brazilian rice crop is concentrated in the

South, with 9.72 million tons, followed by

the North (1.14 million tons), Center-West

(636 thousand tons), Northeast (412 thou-

sand tons) and Southeast (with only 55.4

thousand tons). “Areas suitable for agri-

culture, tradition, rice farming, a good pro-

cessing structure and technology account

for this status of the South. This concentra-

tion is likely to soar”, says Embrapa Rice and

Beans chief executive AlcidoWander.

No

euphoria

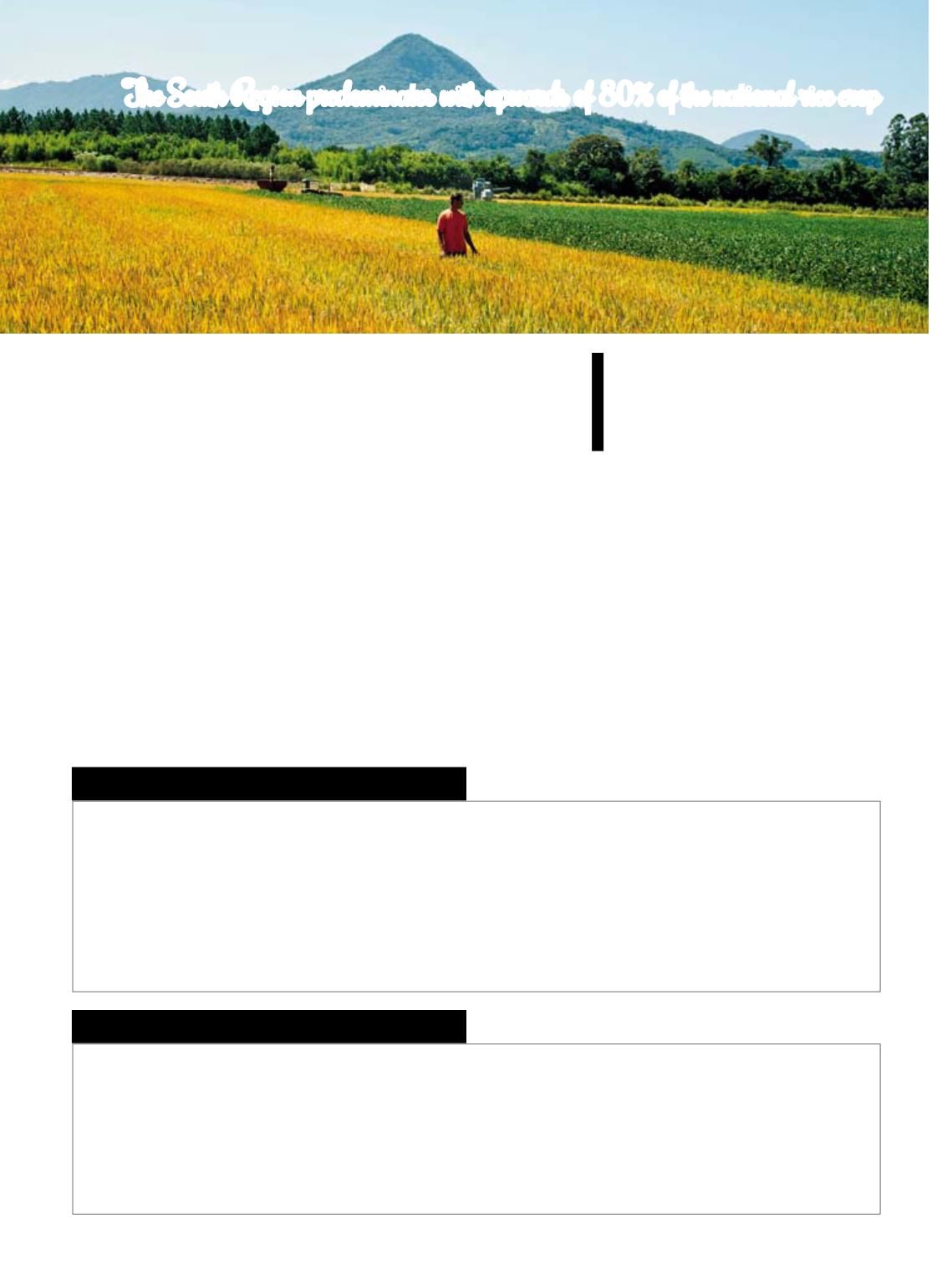

The South Region predominates with upwards of 80% of the national rice crop

Inor Ag. Assmann

16