61

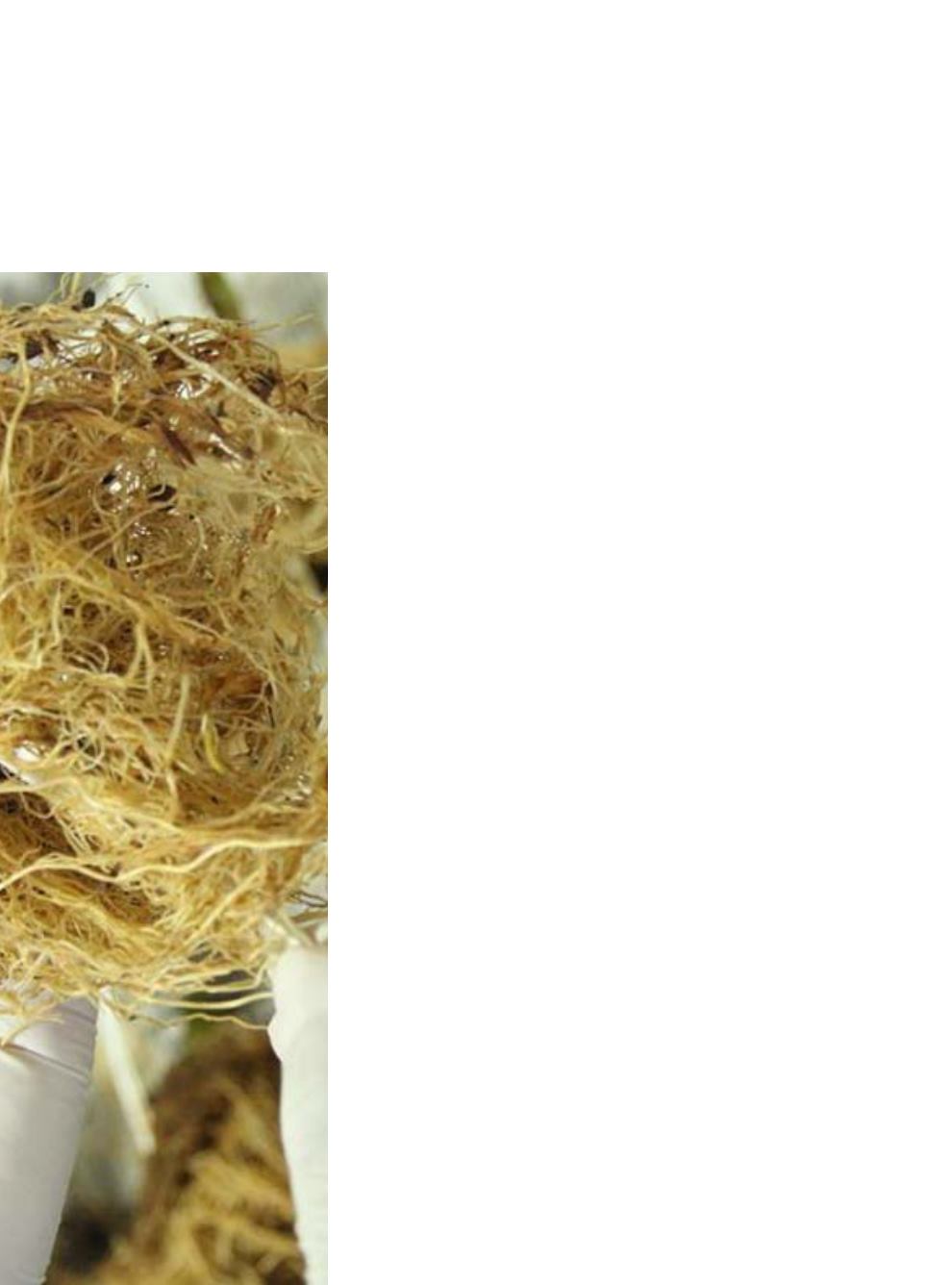

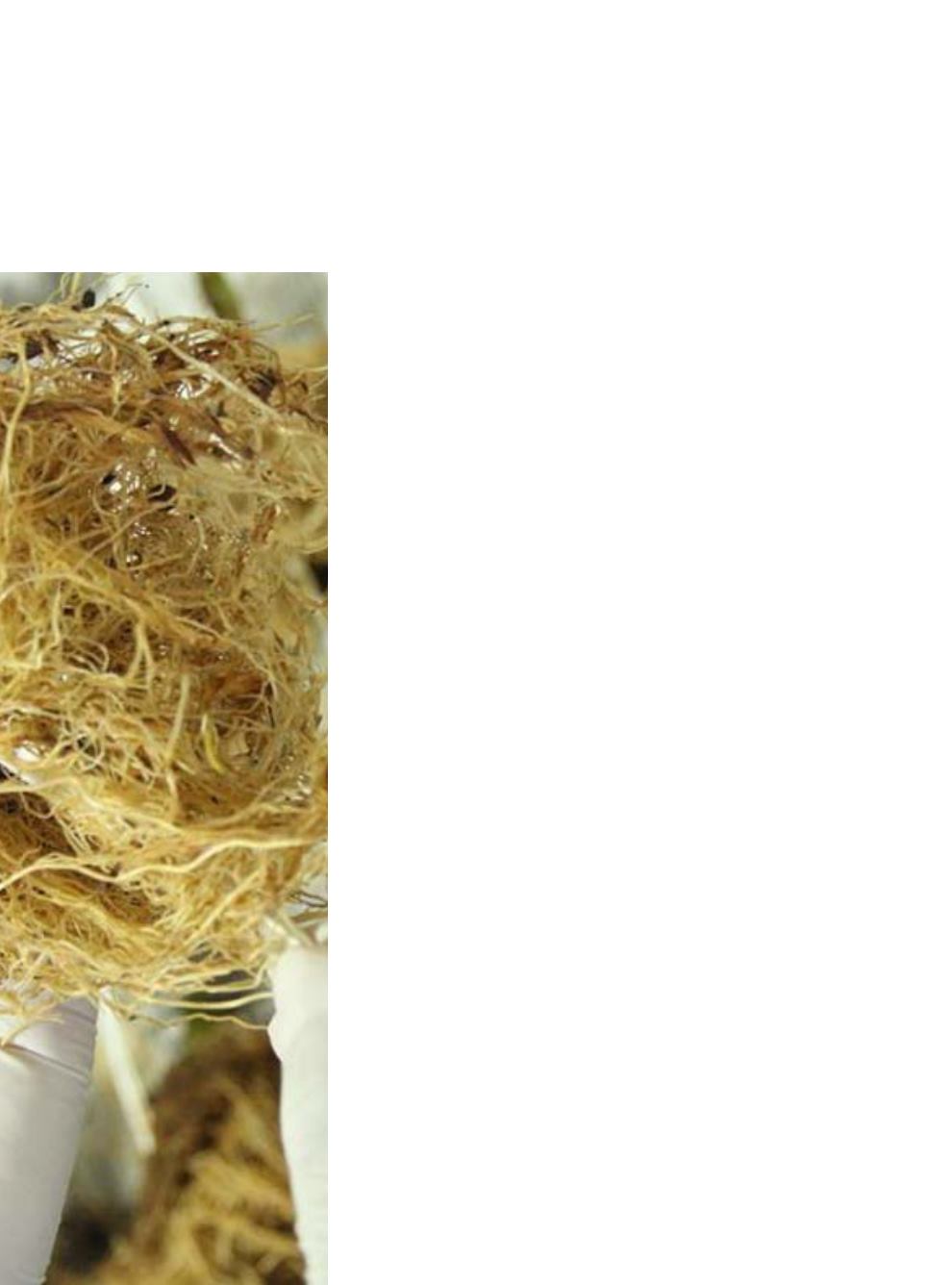

When vegetables are cultivated in the

same area, with no control measures in

place, they frequently do not survive the

intense outbreaks of different root knot

nematode strains (Meloidogyne spp.).

Losses could amount to 100%, depending

on the degree of infestation of the area, on

the nematode strain, on cultivar and envi-

ronmental conditions. Currently, there are

three strains of this soil pathogen group

considered to be the most harmful to veg-

etables (Meloidogyne incognita, M. javan-

ica e M. arenaria). However, there is one

strain that has been causing serious dam-

age to vegetables, and it is phytopatholo-

gy’s biggest concern. The strain in ques-

tion is known as Meloidogyne enterelobii,

of the root knot nematode family, for

which there is no resistance gene in the

currently grown vegetables.

According to agronomist Jadir Borges

Pinheiro, researcher at Embrapa Vegeta-

bles, the strain was first detected in Bra-

zil in 2001, in guava plants, in the states

of Pernambuco and Bahia, causing much

damage to the commercial crops of this

fruit. After reports of outbreaks in the

Brazilian Northeast, in 2006 this nem-

atode was detected in vegetables in the

State of São Paulo, affecting cultivars re-

sistant, up to that time, to other strains

of root knot nematodes prevalent in the

Country. “Besides spreading rapidly, M.

enterolobii infects a big number of host

plants, including a variety of ornamental

plants, tobacco and soybean”, he says.

Pinheiro reiterates that the strain is now

present in most states, but information on

how it affects infected vegetables, intend-

ed to reduce future problems, is scarcely

available. “One of the big challenges, along

with plant enhancement efforts, consists

in the development of resistant cultivars

for managing this nematode”, he explains.

At Embrapa Vegetables, in Brasília, artificial

inoculation is carried out in a controlled

manner in tomato varieties and other veg-

etable species, with the aim to identify re-

sistance sources. At the end, the idea is to

come up with a tomato cultivar, either in-

dustrial or table tomato, that could be pro-

duced in infected areas, as is the case in

the interior of São Paulo.

“Once we find the resistance gene that

contemplates this specific species, the

farmers can plant it and put up with this

problem, once nematodes cannot be erad-

icated”, the nematologist says. In his view,

the use of resistant cultivars is advanta-

geous in that it does not require any ad-

ditional technology and, as a result, has a

low cost and hardly any impact upon the

environment. “The nematode resistance

sources identified so far have not been

thoroughly studied, if compared to the ex-

isting genetic diversity, especially in vege-

tables”, he explains.

Besides the development of resistant

cultivars, the specialist points out that the

challenges also include research on other

plants that are antagonists of the Meloido-

gyne, the succession or crop rotation study

in the management of M. enterolobii and

other practices and technologies that could

be used in infected areas, for correct and

sustainable management of these parasites.

“In Brazil, the problems caused by nema-

todes in vegetables are all the more serious

because of the cultivation of huge areas and

intensive vegetable cultivation throughout

the year, few professional trained in nem-

atology techniques, lack of strict quarantine

legislation and because of the shortage of

resistant vegetable cultivars”, he ascertains.

(In)visible problem

Meloidogyneenterolobii challengesnematologywithintheolericulture

contextandpromptsthepursuitofcultivarsresistanttothestrain